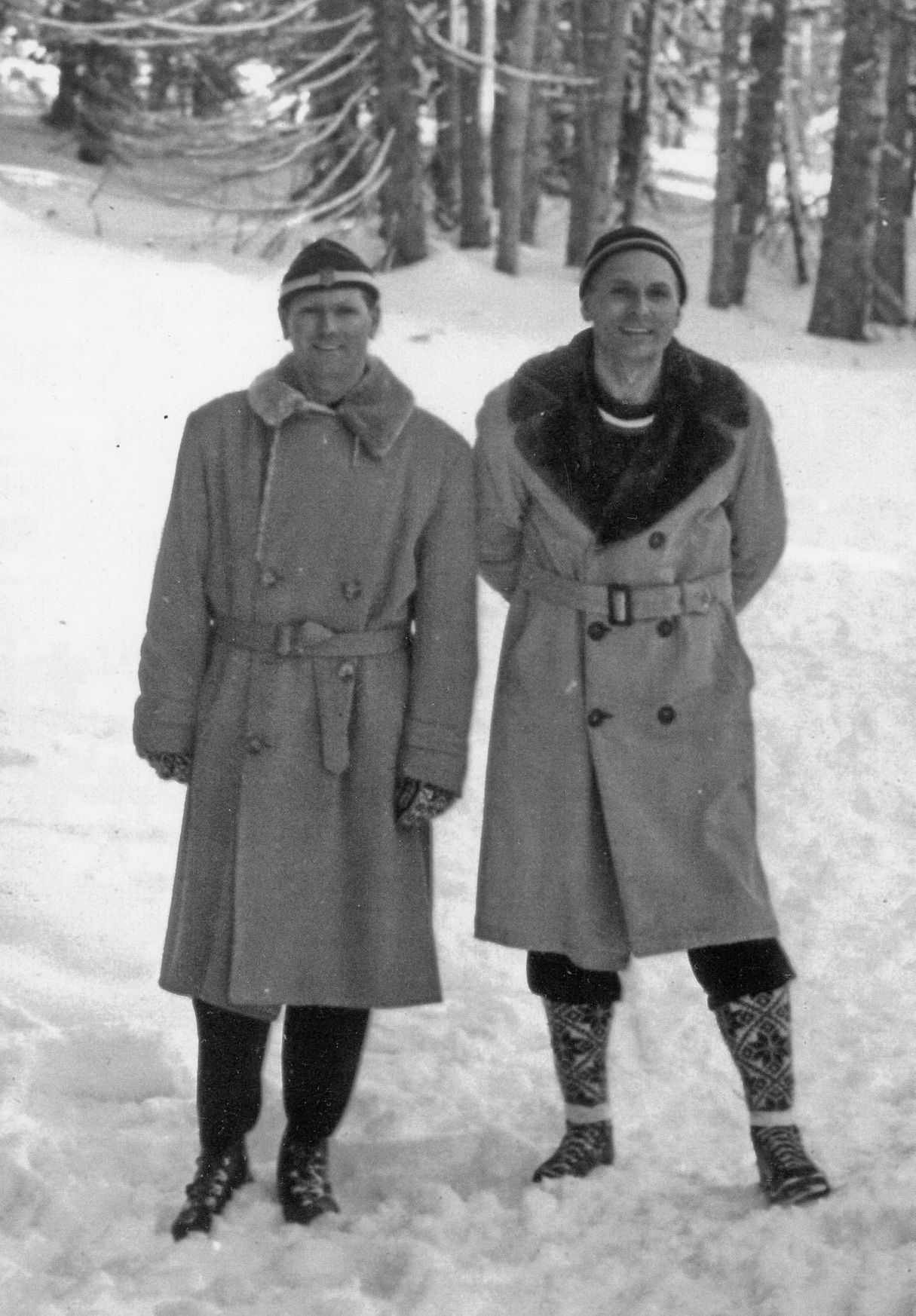

01 – Chief of Course Wendall Broomhall (l) and Chief of Race C. Allison Merrill. Courtesy Wendall Broomhall.

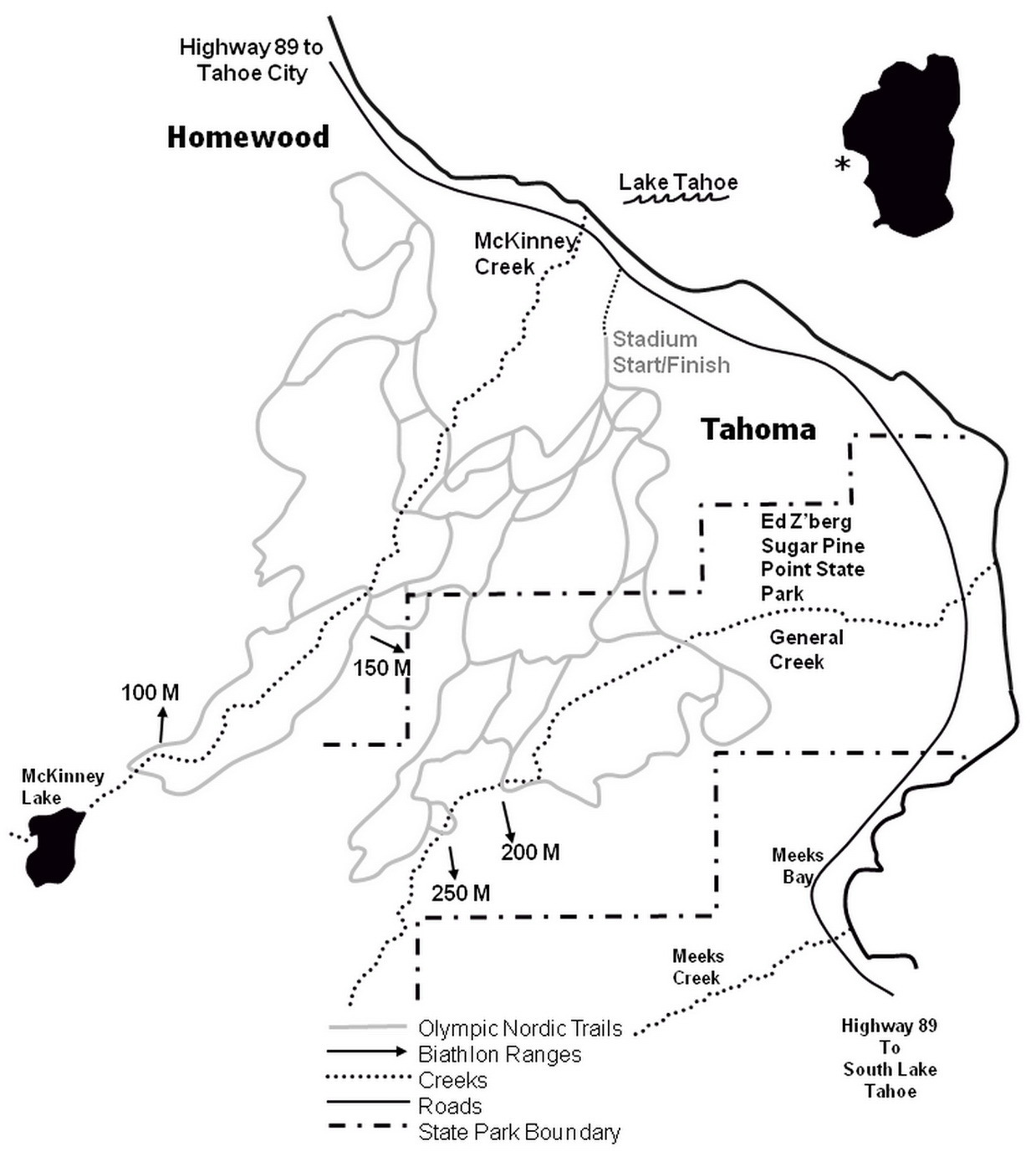

02 – Map showing Olympic cross-country trails and shooting ranges at McKinney Creek cross-country venue. Courtesy California State Parks.

03 – Restored Tucker Sno-Cat used to groom McKinney Creek cross-country trails. Photo by David C. Antonucci.

04 – A biathlete shoots at the 200-meter range during the 1959 North American Championships on the McKinney Creek biathlon course. Photo by Bill Briner.

While Squaw Valley had been considered as the location for the events, it was determined early on that the proposed and recent development in the valley could not support them. The valley was especially unsuited for the inaugural 20-kilometer modern winter biathlon, with its expansive shooting ranges and safety zones. Wendall “Chummy” Broomhall, a former U.S. Olympic cross-country skier and 10th Mountain Division veteran, was hired to survey the valley, and initially determined it was suitable. However, when it was determined to be unsuitable due to encroachment of private development and Olympic facilities, he had to find an alternate location. The perfect location turned out to be at McKinney Creek, 16 miles by road from Olympic Village on Lake Tahoe’s west shore where the IOC had previously approved the venue for the newly added biathlon competition.

Scandinavian countries opposed the changes and threatened to sink the Winter Games by withdrawing and holding their own cross-country events if changes were not made. Their complaints revolved around elevation, snow conditions, and travel distance from Squaw Valley.

Ultimately, Broomhall successfully defended the relocated courses, and all parties agreed to a pre-Olympic competition, the North American Championships, in 1959 to verify the adequacy of the facilities.

The McKinney Creek venue consisted of 65 kilometers (40.4 miles) of trails, stadium, and support buildings. Organizers erected temporary structures for race administration, communications, timing, press, equipment storage, and ski preparation, in addition to a scoreboard and bleacher seating for 1,000 spectators. The Organizing committee retained Broomhall as Chief of Race, and C. Allison Merrill, a Dartmouth ski coach, as Chief of Course for design and supervision of construction of the cross-country skiing venue.

Only recently inducted in 1957 as an official Olympic sport, the modern winter biathlon competition would have its debut at the 1960 Winter Games. The course required four different shooting ranges with firing stations for 15 competitors at each range. Chief of Race Birger Torrissen, a former U.S. Olympic Team member and coach, laid out the ranges, and Broomhall and Merrill connected them with trails.

The wide ranges of winter temperatures and their effect on snow conditions provided a difficult challenge for Broomhall. Daytime temperatures near 40 degrees Fahrenheit melted the snow

surface, while overnight cold refroze it into an ice-like hard surface. Since the usual method of course preparation wasn’t working, Broomhall conceived of a device that would mechanically pulverize the snow surface, thus restoring its granular nature. Broomhall’s device, which involved mating an agricultural grain flail to a 40-horsepower gas engine, all mounted on a pair of snowmobile runners and towed behind a Tucker Snow-Cat, was the first documented application of a powered tiller groomer in the ski industry.

As the North American Championships of 1959 approached, Broomhall and his team were especially eager to prove the quality of the McKinney Creek venue and quell the skepticism expressed by the Scandinavian countries.

During the Championships, while nearby Olympic Village accommodated the would-be Olympians from 14 nations, the McKinney Creek venue hosted men’s and women’s cross-country races and the 20-kilometer biathlon. A series of storms battered the Sierra for 10 days leading up to the competition, dropping nine feet of snow on the valley floor and much more on the mountains. American ski filmmaker Warren Miller was there to capture the action that later appeared in his 1959 movie, Let’s Go Skiing, and Marvin Brecker Films—which would produce the official 1960 Winter Games documentary—was there to shoot the Olympic promotional film, Westward the Flame.

Yielding new world records and top wins, the North American Championships were a resounding success in the American tradition of excellence, and they did much to quell the anxiety of many still unconvinced European nations. Most importantly—and most gratifying for Broomhall and his team—Knut Korsvold, FIS technical delegate, calmed Scandinavian worries about the McKinney Creek venue when he stated he was “extremely well pleased.” The trial confirmed the McKinney Creek venue as a worthy and formidable stage for the Olympic Games.